Szmul Dawid Grosman

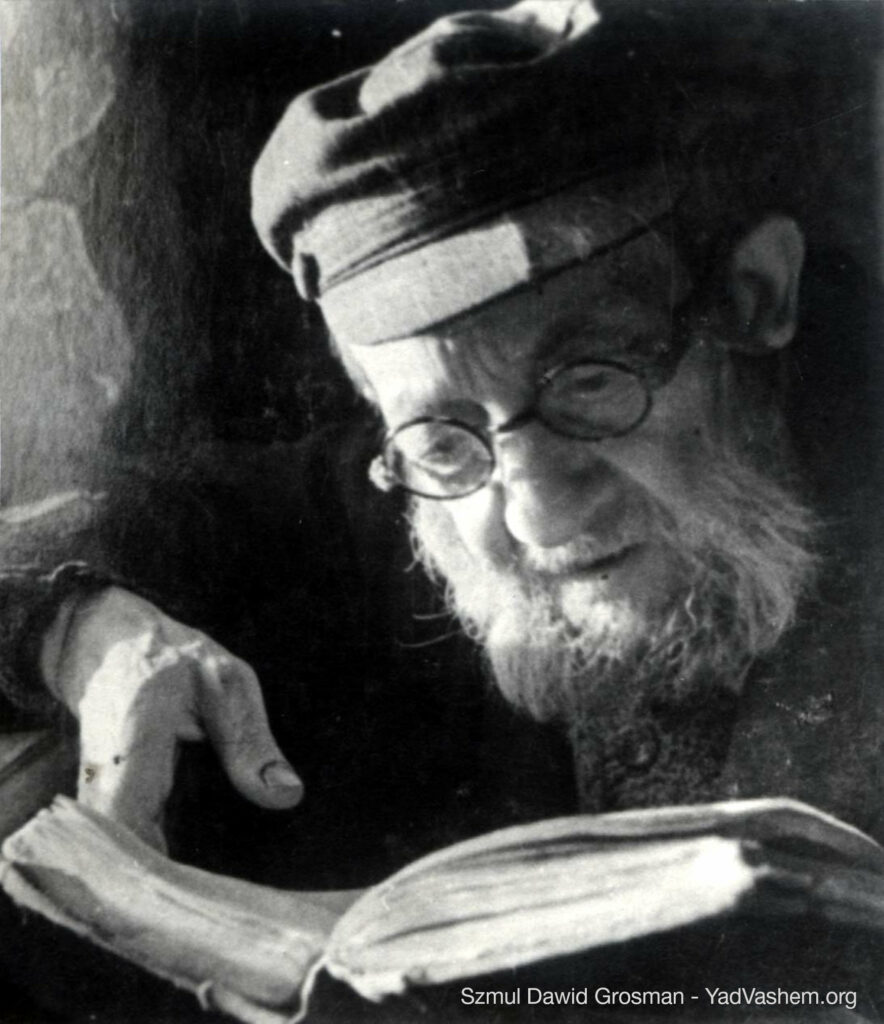

I recently watched a video tour of the Yad Vashem Memorial in Israel. One of the gentlemen involved in this project suggested that each of us choose a name from their list of holocaust victims and investigate who they were; to ensure that those lost in of one of the worst atrocities of human history be remembered by name, and not relegated to a number in a database, or tattooed on the arm of the fallen. I visited this database of victims, and on the opening page was a slideshow of photos of many of these people. Some were images of young, happy families taken before the war, all of them a sobering reminder of the horrors mankind is capable of. One image in particular struck me, the photo of an elderly gentleman sitting by a window intently reading from the pages of a book, “Szmul Dawid Grosman”.

This photo appears to have been taken sometime in the early 1940’s — Mr. Grosman born in 1882 and he would have been approaching the age of 60. Seeing the deep lines on his face he appears at first to be much older; one of the many side effects of starvation. Szmul was imprisoned in the Lodz ghetto of Poland during the war, where tens of thousands of Jews were interned on their way to Auschwitz or the Chelmno death camps. They were given meager rations and forced to labor to provide material support for the Reich’s war effort. Those who were too young, too sick, or too old to handle the rigors of work were the first sent off to the gas chambers.

The grit of this labor is seen encrusted on the fingernail of Mr. Grosman, his thumb hovering gently as he leans his book toward the light from a window. Szmul appears entranced by what he’s reading, his eyes revealing an intense focus on these pages; and I imagine him trying fervently to wash his hands before opening this tattered but seemingly valuable document. Perhaps it’s his daily routine as the early sunlight shines through his window, a respite before his day of hard work begins. Despite being a black and white image, it’s clear his ragged beard is gray; there is a certain air of wisdom and strength in his face, yet what seems an uncertainty which likely weighed heavily on all of the Jewish people throughout Europe during the war. The exhaustion of the years of forced labor must have taken their toll on him. Yet Szmul perseveres to ensure his name won’t be on the next list of the fallen who’s bodies and wills had given out. But just a year or two from when this photo was taken, this fearful reality will visit Szmul as well.

Mr. Grosman’s mouth is open, perhaps he’s reading aloud to his fellow residents at 55 Kelm Strasse, flat 12. Chana Ruchla Grosman is also listed at this address, 5 years his junior and Szmul’s wife as attested to by Shoshana Zilber who identified herself as his daughter. The photo was taken by Mendel Grosman, one of Szmul’s sons and a photographer whose work was found after the war. Thousands of illegally taken photos were hidden, images of the harsh world of the Lodz Ghetto; the kind of photographs the Nazi regime had forbidden. There are seven names listed at this address, covering three generations of the Grosman family; his children in their late 20’s and even his grandchildren just a few years old. Perhaps he reads for his family each morning as they share their rations; often the elders would go hungry to ensure the children were fed. His steady voice giving comfort to his loved ones as he reads the words from his book. I assume it’s wintertime and his flat is cold, Szmul’s wearing his hat and coat over what appears a heavy sweater. Just out of the frame of this picture or maybe behind his book, I imagine a yellow patch in the shape of the Star of David stitched to his coat; the same star featured today on the flag of Israel. The furrow in his brow above his glasses as his old eyes, like mine, struggle to focus on letters printed in books. Yet the more closely I examine this old photo, the more I notice a sort of serenity and perhaps even a faith found in the well worn pages of his book. I wonder if Szmul is reading a Tanakh – the highly esteemed book of the Jewish people we call the Old Testament – and maybe it’s opened to that cherished Psalm, as he encourages his children with those familiar words:

The Lord is my shepherd, I will not be in need. He lets me lie down in green pastures; He leads me beside quiet waters. He restores my soul; He guides me in the paths of righteousness For the sake of His name. Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I fear no evil, for You are with me; Your rod and Your staff, they comfort me. You prepare a table before me in the presence of my enemies; You have anointed my head with oil; My cup overflows. Certainly goodness and faithfulness will follow me all the days of my life, And my dwelling will be in the house of the Lord forever. ~ Psalm 23 NASB

I can only speculate on the circumstances surrounding this photograph, yet it seems to say so much with so little. Tragically Mr. Grosman was killed in March of 1942, and his wife soon after in July, his children seem to have held on another few years. I wonder if each morning after their parent’s departure, they read these same words from this tattered old book, the faint sound of Szmul’s steady voice in their memories. I cannot fathom the magnitude of their struggle, or the strength of this man’s character as he labored for the last years of his life. What I can say, is that Szmul Dawid Grosman isn’t just record number 4521934, he’s a man who’s face is now etched in my memory. I know very little about Mr. Szmul Dawid Grosman, except that he was a father, a grandfather and a husband; and the owner of a book.

Szmul Dawid Grosman, 1882-1942

All personal details about Szmul Dawid Grosman and his family are derived from historical documents provided by Yad Vashem. For further reading or to explore the lives of other Holocaust victims, please visit the Yad Vashem website where these records are meticulously preserved.

1 Leave a Comment

Belinda –

Mike, This Is Outstanding. Keep writing.